Semantic Fluency Tasks

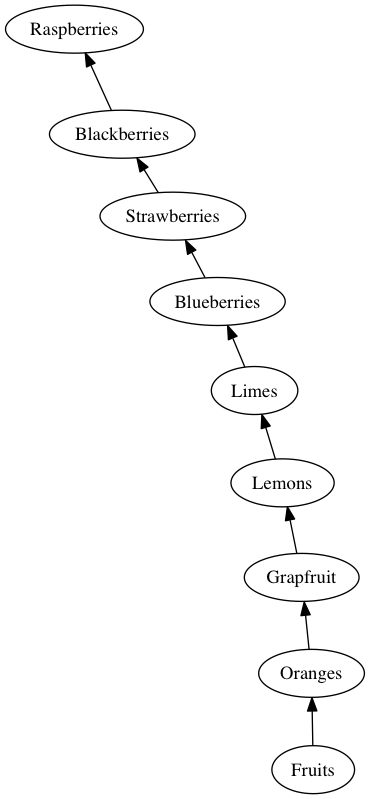

Figure 1. Linear naming in the Semantic Fluency Task.

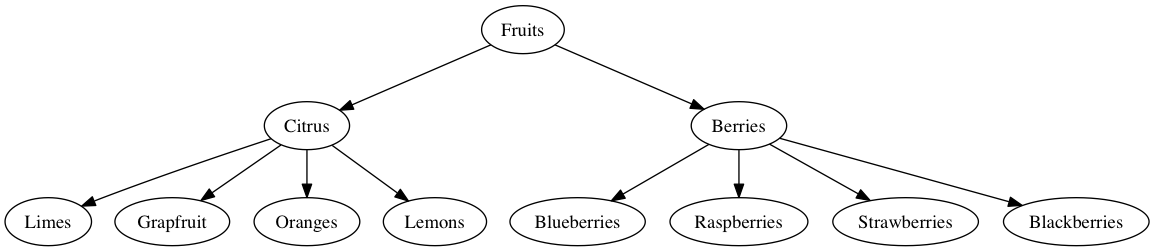

Figure 2. Hierarchical clustering in the Semantic Fluency Task.

Figure 2. Hierarchical clustering in the Semantic Fluency Task. In the Semantic Fluency Task, you hear a word like "fruit", and then you need to name as many words as possible that belong to that category, relying only on your memory.

When you do this, do you activate all the words you know at once? Or maybe, some large set of related words? And then iterate over the words in the list, naming them one by one? (Figure 2.) Or do you activate one item, name it, and then continue to name the next item? (Figure 1.)

At an even more abstract level, do you use a parallel processing or a serial processing strategy to complete the semantic fluency task?

If you dont' know, a Parallel Processing means that a task can be divided into distinct processing threads, and each thread can occur independently of the other thread. Serial processing, on the other hand, implies that the task requires a single thread, and processing has to happen in stages of the single thread.

For the Semantic Fluency Task, Troyer and Moscovitch (1997) review evidence that people use a combination of parallel and serial processing. In their account, you'd activate a list of related items all at once, iterate over the list, and then, you'd switch to the next list. So, in Figure 2., you might see the word, "Fruit", and then you'd activate a bunch of different dictionaries like,

{"Citrus": ["Oranges", "limes", "grapefuit", "lemons"]} {"Berries": ["Blueberries", "blackberries", "strawberries", "lemons"]}This combined strategy accounts for the common observation that participants pause between burst of semantically related lists of items. But the most important point is that dictionary keys might be activated by a thread that runs in parallel to the thread that produces items from the dictionary, which runs, of course, in serial. Interestingly, serialization is imposed by an external constraint: subjects must name all items in time. So while access to items might occur all at once, the fact that we have a serial iteration of items is just a result of our computation unfolding in time.

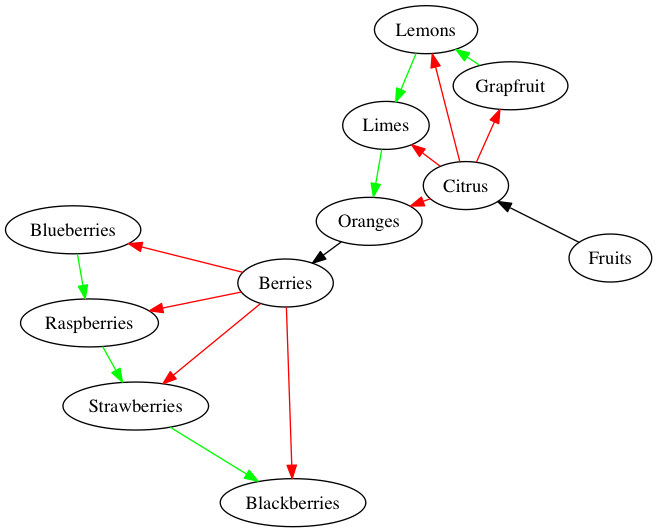

An alternative to this story is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Red edges show simultaneous activation of items. Green edges show serial iteration through nodes in a cluster. Black edges show priming from node to cluster.

Here we still have activation of a single key value, which activates clusters, but after iterating through a cluster, the most recent item primes the next cluster (from oranges to berries), which gives rise to the next dictionary (e.g. cluster of related items). What’s parallel about this strategy is that there may be a thread that gets updated while another thread is iterating through items in a cluster. As the thread updates, it starts to weigh more heavily toward a new key target (e.g. a target for the next key in a cluster). In Figure 4., I show this explicitly with blue edges, and a ? node.

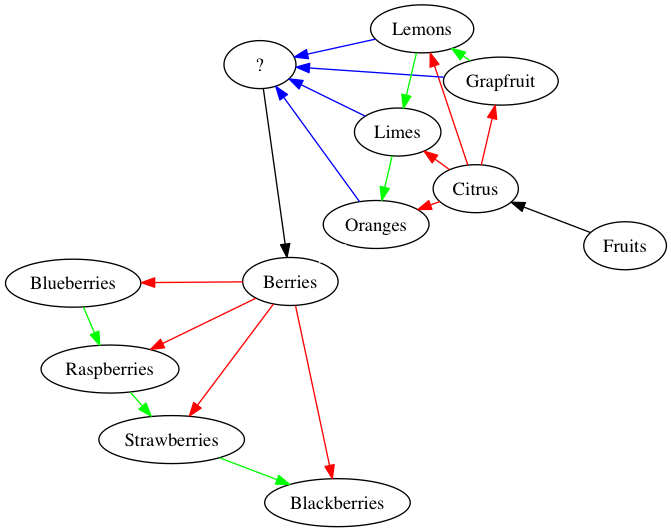

Figure 4. Blue edges denote an updating process for the prime

So here, the question node (?) gets updated in parallel (Blue edges) to the thread that iterates over the nodes in a cluster (Green edges). The ? node, whatever it is, then serves as the prime for the next target for a key in a cluster (Black edges).

Personally, I think this is what happens in the Semantic Fluency task, and I think Figure 4. goes a step in the right direction toward formalizing what is involved in the task at a cognitive / functional level.

References

Troyer, A. K., Moscovitch, M., & Winocur, G. (1997). Clustering and switching as two components of verbal fluency: Evidence from younger and older healthy adults. Neuropsychology, 11, 138–146.